The evolution in the portrayal of “selfish” female Disney characters is a worthy case study for how the feminist movement has progressed over the seventy-five years from Snow White to Frozen; the operative definition of selfish from Merriam-Webster being, “concerned excessively or exclusively for oneself.”

Each “selfish” female character embodies and reveals the expectations placed on women by society en masse in their respective time periods – the anxieties and ideals society had surrounding what a woman could be – while also perpetuating those biases for the next generation. This post will be the beginning of a series each discussing one to two such “selfish” characters.

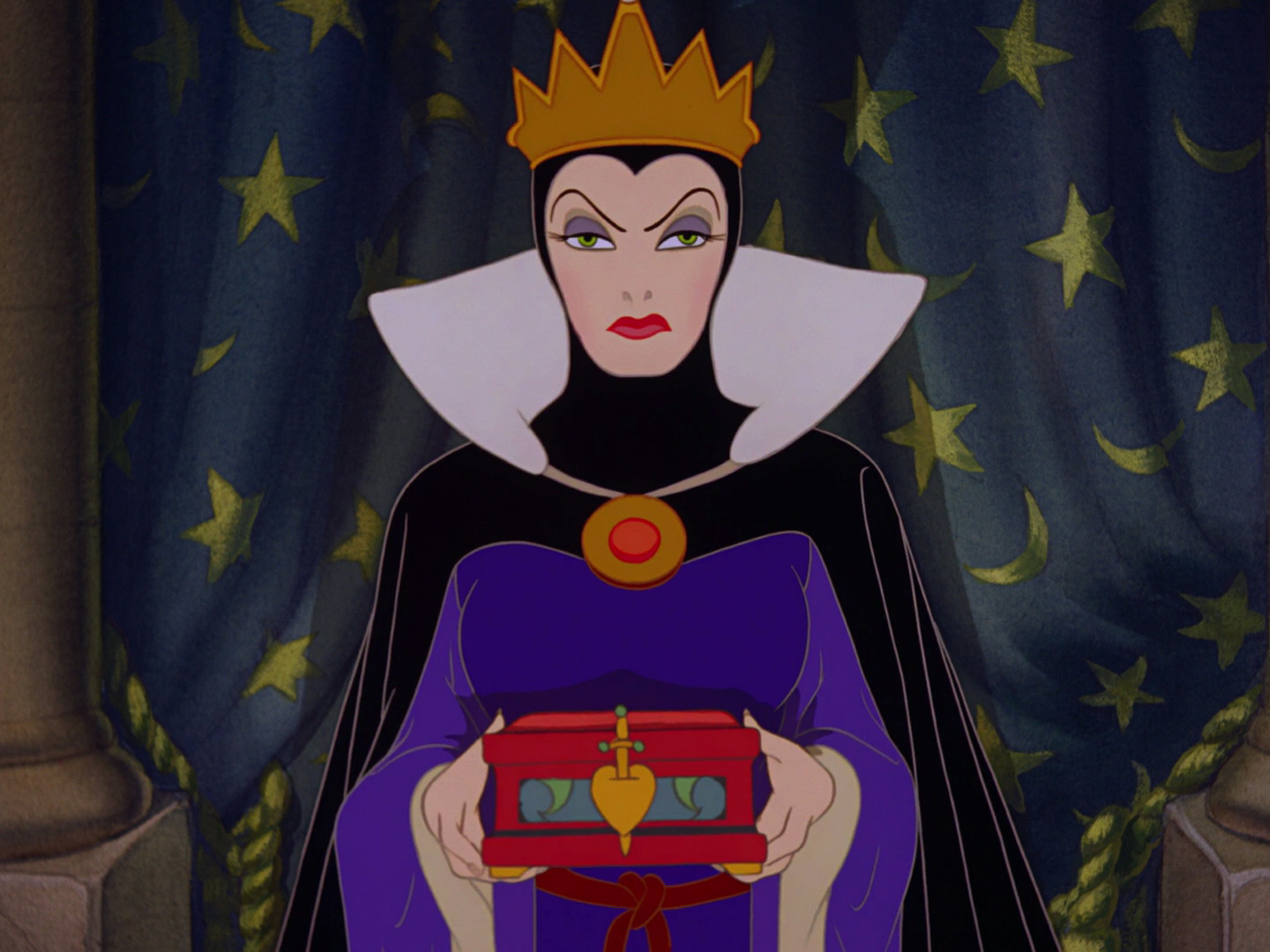

The label of “selfish” is a loaded one for women, a scarlet letter that they are raised to recoil from at all costs, because caring selflessly for the needs of others is considered a foundational tenet of femininity. Deviating from this contemporaneous societal definition of caring selflessly was the Evil Queen from 1938’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, who was driven by a desire to be “the fairest one of all.”

This is a phrase which, like selfishness, touches upon something that is an innate aspect of the female experience. It implies competition between an entire gender because, as women, attractiveness is a key component towards determining our value as human beings, especially at the time that Snow White was being developed and released.

“I think Snow White is the perfect embodiment of 1930s culture,” said art historian Carmentina Higginbotham. “In cities, when you’re pushing up against an increase in office girls or office women, you have more women working because of the Depression, you have a push towards-not necessarily social equality-but sort of a psychological equality that women are contributing. They are working very hard and Snow White, more than any other of Disney characters, is rooted in a ‘30s aesthetic. So she looks very much of the period even though the film is set in an indeterminate time.

She is not a revolutionary character, but she’s spirited and she uses her skills and traits to the best of her abilities. Snow White has a beauty that is obvious to her. She’s very humble about it. She’s not overtly sexual. This is an ideal 1930s woman-beautiful, aware of it, but not pushing for social change.” In other words, Snow White was an amalgamation of the desires the male workforce had for their newly hired, subordinate female co-workers: Be effortlessly pretty, present yourself as chaste, do the work we give you with a smile, and shut up.

If Snow White was the ideal 1930’s woman, then narratively her antagonist, the Evil Queen, had to stand as her direct opposite. Where Snow White was depicted as passive, and thus a throughline was implicitly drawn between passiveness and goodness in women, the Evil Queen had to be assertive, thus creating a link between assertiveness and evil/wickedness. Where Snow White was the fantasy, the Evil Queen was the nightmare.

“Looking at the characters from this archetypal standpoint, Snow White and her antagonistic wicked stepmother can be interpreted as light and shadow sides of the feminine psyche. The two are connected by their mutual need to be young and beautiful…”, wrote Arielle A. Silver in her Master’s thesis. This is perhaps better understood as an extension of the Madonna/Whore dichotomy, which states that all women are to be evaluated through the patriarchal gaze as either an “angel” or a “devil,” with little to no nuance in-between.

Silver went on to refer to a blog excerpt on archetypes which expanded upon the idea: “…Strong women are often discriminated against. Female politicians, prominent feminists, and leaders are judged on their appearance and personality, their very femininity is called into question time and time again. They are shaped into the evil step-mother or the witch, representing, in the outside world, this part of the psyche that is so difficult to manage.”

Dorothy Ann Blank, the only female storyboard artist to work on Snow White, experienced such villainization quite literally. In the book The Queens of Animation: The Untold Story of the Women Who Transformed the World of Disney and Made Cinematic History, author Nathalia Holt recounted Blank’s experience: “[Character designer] Joe Grant had become obsessed with Dorothy’s image.

She frequently saw him sketching her from a porch nearby, periodically staring at her before returning to the page. Most new hires would have shied away from his gaze, afraid to disturb the dynamics of the story department and possibly become the target of pranks, but Dorothy was rarely afraid of anyone. ‘What are you doing?’ she asked him bluntly when she noticed him watching her. ‘You are an inspiration,’ Joe replied with a smile, but Dorothy was not so easily mollified.

‘But why are you sketching me?’ she demanded. ‘I’m modeling your face for one of our characters in Snow White.’ ‘Which one?’ ‘The evil queen,’ Joe replied curtly… Thanks to Joe it was not merely Dorothy’s words that would find a permanent home in the film, but her face as well: her arched eyebrows, her almond-shaped eyes, and her long, straight nose were all reflected in the face of the beautiful but vain and wicked stepmother.”

Blank was a woman in her late ‘30s at this point, presumably in possession of a family of her own, but she was considered selfish enough to be a villain by men because she took up a position of power that could have been given to a man supporting his family.

The Evil Queen was considered selfish because she was a woman who not only wanted, but wanted more than her allotted share and labored to have it. She desired the most beauty because she understood that, as a woman, it meant being in possession of the most power.

It’s what differentiates her from “perfect” Snow White – while Snow was happy to spend her days as “the fairest of them all” cleaning house for working men and singing to birds, the Evil Queen worked for no one but herself. As exemplified by the dynamic between Joe Grant and Dorothy Ann Blank, the average male of the 1930’s held women in possession of such self-assurance in great contempt.

And has that changed as much as we want – and need it to?