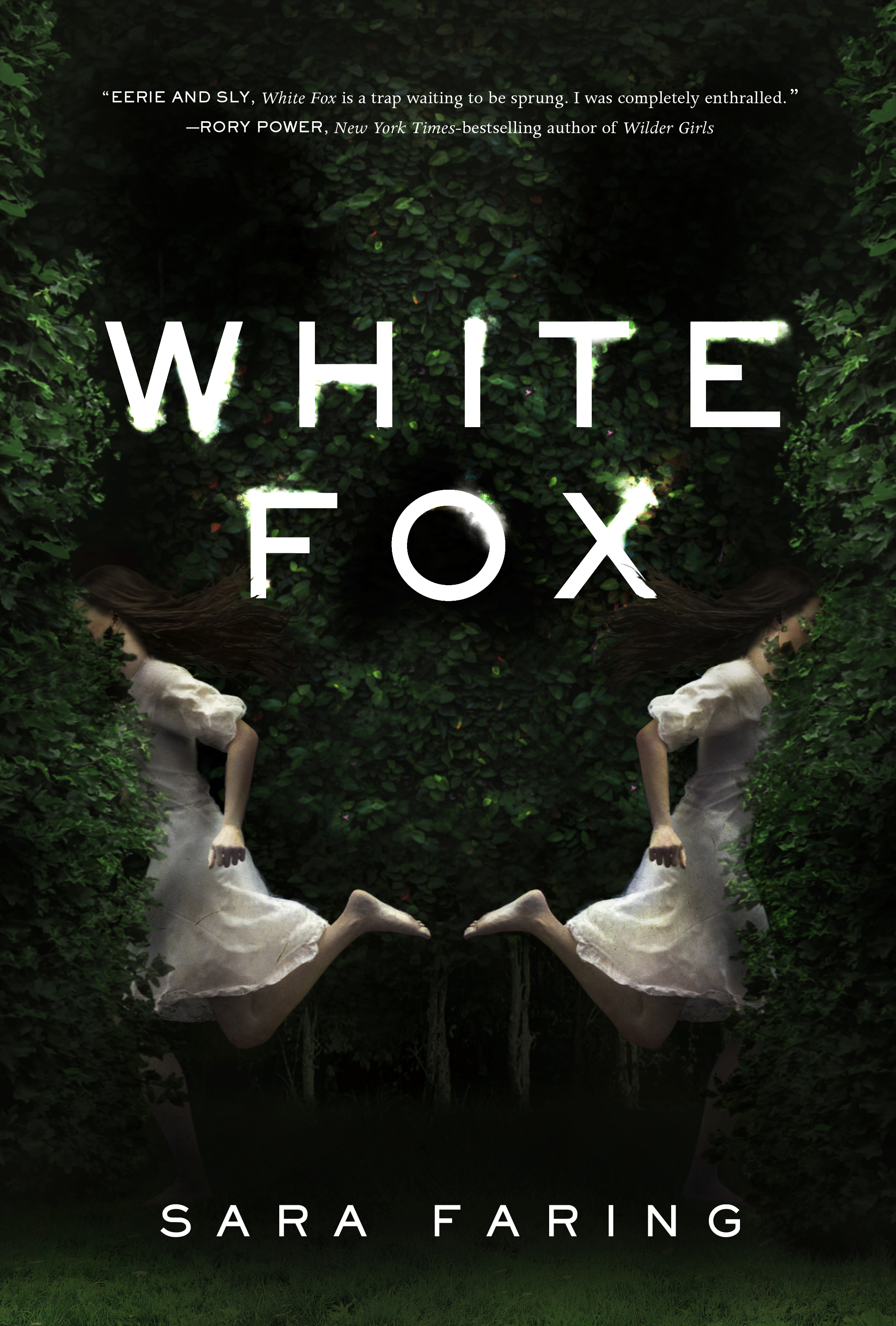

You know that we love a good read and White Fox looks very intriguing to us.

If you haven’t heard of the book here’s the synopsis-

After their world-famous actor mother disappeared under mysterious circumstances, Manon and Thaïs left their remote Mediterranean island home—sent away by their pharma-tech tycoon father. Opposites in every way, the sisters drifted apart in their grief. Yet their mother’s unfinished story still haunts them both, and they can’t put to rest the possibility that she is still alive.

Lured home a decade later, Manon and Thaïs discover their mother’s legendary last work, long thought lost: White Fox, a screenplay filled with enigmatic metaphors. The clues in this dark fairytale draw them deep into the island’s surreal society, into the twisted secrets hidden by their glittering family, to reveal the truth about their mother—and themselves.

We’r excited to bring you an exclusive excerpt from the book by Sara Faring.

This won’t be super bubbly and fresh like I want it to be, but life ’s only like champagne in that it can be not-so-easy to digest sometimes, right?

Here ’s the truth: My parents each gave me a secret from the world, one beautiful egg of a secret each that I’ve carried with me since I was a snot-nosed kid, very, very carefully, so they would never crack.

Dad told me I was born with the mark of luck on me. It came in the form of this gross little fatty deposit at my temple—Mama had it removed by a plastic surgeon when I was a year old so I wouldn’t be teased, thank God—but Dad told me the luck itself would never leave me, and . . . it hasn’t.

And Mama: She used to take me up the ladder to the tower hidden in her bathroom, to the nest with the view of the forest that was only ours.

I was her special baby girl, and this was our special place.

She would wrap me in a cozy blanket, and cuddle me, and read to me from books like The Twenty-One Balloons, which she stored in a metal box, covered in foil animal stickers I had insisted we buy from this airport kiosk in Frankfurt.

The secret grew when she left. I knew she might have left a mes- sage for me there, but the room was locked and closed so that no one could enter. I couldn’t tell Dad or Nons, because it was our secret place. Ours alone, and telling them would ruin it.

And I wanted to be the one who found her message, anyway.

I planned a lot in secret, in the days after she left. I was so god- damn industrious. I planned how to break into her bathroom (a set of master keys from Dad’s Stökéwood office, where he slept most nights). I planned how to reach the rope coiling down from the ceil- ing (a step stool), and I planned how to pull and hold the attached ladder down (a hand weight from the creepy old home gym).

I put my plan into action, one rainy night, when Noni was curled on her side in bed, refusing to speak to me, and Dad was talking to Uncle Teddy downstairs.

Reaching the magazine box at last, I shut my eyes as I placed my fingers around the rusted latch.

It opened easily.

But it was . . . empty.

I scrabbled around the bottom, sure I was missing a compartment, and I knocked the flashlight off the ledge with my elbow. The jolt of it hitting the marble floor below broke me into sobs, thick, hot, wet tears that streamed out of me because I no longer cared if I was found. My hunch, the one I had so carefully tended, was wrong.

Mama had left me nothing.

It was one of the students from the institute—a part-time assistant to the family—who found me crying up there. In those

days, they helped Dad with us, with everything, and he called them all Boy, which I recognize now was colossally fucked. This young guy helped me down, and I made him swear on his life he wouldn’t tell anyone about the secret tower. He shrugged, probably thinking I was just some silly kid, and ruffled my hair before helping me off to bed.

The whole experience rattled me. I never snuck back into her bathroom again, at least not before we were shipped off to the States.

But if Dad did see Mama, and she had been back to Stökéwood since . . .

She might have left a message there for me. Where she knew only I—not Dad, not Manon—could find it.

So, as soon as Manon ditches me—as I suspected she would—I blast disco music saved on my phone and I slink around the stacks of moldy paperwork and make my way up the creaking grand stair- case, past the moth-eaten velvet rope used to keep visitors away. It’s actually cleaner than I thought, besides the nasty plate of withered fruit in the halfway and an actual shag carpet’s worth of dust. The electricity works, even if some of the bulbs flicker. What’s spookier is that the upstairs furniture has been sold off, but you can see the stained divots in the carpet, where the legs stood. My empty bedroom has been repainted asylum white, and everything in Noni’s bedroom has been replaced with just two crisp white cots that could probably only fit me with my arms folded over my chest like a mummy. I find an old Spirited Away poster of Noni’s rolled up in her closet, next to a useless, yellowed wall calendar with horrible, off-kilter drawings of old Viloki castles from 1988. Stökéwood is Miss December. Blasting ABBA, I prop both against the wall for pizazz, before edging toward Mama and Dad’s bedroom.

The door is stuck—not locked, I don’t think, but jammed— which sends a shivery ache through me. It also smells like a small

animal died from starvation in the vents while watching endless sea- sons of Love Island. I raise the music’s volume to keep the wrong kind of ghosts away.

The good news is, I can still access Mama’s closet because it has a separate entrance on the floor. That’s how big-ass it was. Most of its once-sparkling contents have been stripped away and auctioned off, but I can actually smell lavender in the cedar corners if I close my eyes. I find the secret cabinet that seamlessly blends into the wood, and it clicks open softly, revealing a couple of halfway-decent vin- tage pieces, forgotten for all these years. They probably need major dry cleaning, but I still spend too long running my fingers over their intricate beading and imagining that maybe she was the last person to touch one of them.

Then, with the feel of those nubs still imprinted on my hands, I push through to her private bathroom for the first time in a decade.

Her personal effects are gone—some went to me and Nons, like the glass bottles and gilded jewelry bowls and luxurious signature cosmetics, for us to spritz and spread onto our prepubescent bodies, to feel her close for just a minute even though that was probably a giant waste of La Mer—and others were just disposed of, I guess. The green-veined marble, which always looked like frog skin to me, is so cool to the touch. I turn the golden fleur-de-lis-shaped sink handle with a rusty squeak: The water spatters amber for a minute, then runs clean.

With my fingers, I work my way under the sink, toward the latch behind the false panel.

It’s still there.

My nerves are the size of elephants in my stomach. I could vomit, but I don’t want to clean, so I swallow five times, then take a quick yogic breath of fire and press down on it. And wait.

I hear a clunk overhead, and the panel in her ceiling exhales and cracks open half an inch.

Jammed.

When I was young, the panel would drop open like an unhinged jaw, and a woven rope would fall through the air, tonguing at the top of Mama’s head. A sick monster is licking you! I would squeal. No, I’m climbing up Rapunzel’s marvelously thick yellow braid, Mama replied, tugging on its greasy length to bring down the ladder.

I run for a broom, for a stick, anything to help me smack at the panel. I find an old chair in the hall. Straining on my tippy toes, I just make it, and with a shooooomf, years’ worth of dust swirls through the space and blankets me, transforming the bathroom into a disgusting and magical space in the low light. Coughing, pulsing with adrena- line, I yank down the rope and ladder, which now seem small—as if made for children.

I feel disembodied as my palms and fingers close around the first rung. The flaking metal stings the skin on my palms. I don’t know if it’ll hold my weight. But it held hers, so I begin to climb, limbs shaking.

The windows in the tower above my head are dark with grime, so it’s impossible to see out as I pull myself up, up, up. I feel, by memory, the first ledge by the window. That’s where she sometimes lay down the blanket for us both to relax on.

“Our tree house,” she whispered to me, and then she would find one of the books we stashed in the black metal magazine storage box, so they wouldn’t get wet if the windows broke when a storm rolled through.

I step onto the ledge, feeling my way around the dark, and that’s when my foot hits something with a clang.

The magazine box.

White Fox comes from Sara Faring. Born in Los Angeles, Sara Faring is a multilingual Argentine-American fascinated by literary puzzles. After working in investment banking at J.P. Morgan, she worked at Penguin Random House. She holds degrees from the University of Pennsylvania in International Studies and from the Wharton School in Business. The Tenth Girl is her debut book. She currently resides in New York City.

White Fox release September 22, 2020.